The Last Picture Show (1971)

In the early 1970s a clutch of films

came out that used mythical American themes of pop culture to ask:

where is America at now?

Peter Bogdanovich's The Last Picture

Show (1971; 1992 Director's Cut) takes place in small-town Texas in

1951. Shot in black and white, the immediate effect is that this is

a lost classic contemporary to the period, in a similar line to

British films such as Billy Liar or The Loneliness of the Long

Distance Runner that dwell on similar aspects of developing

sexuality, alienation, and conflict. The black and white renders

obsolete a staple of films set in the American West: the blue skies

and ochre deserts are dulled into sharp but flat landscapes. Unlike

films were the landscape of the West are used to suggest vast open

spaces and heights of unclaimed space, the town of the Last Picture

Show is pointy and restricting. Filming in this way also calls back

to the “classic” era of American films, but that isn't quite

right as the films that became most associated with black and white

were noirish, stylish films, fast, hot and fluid. The Last Picture

Show is a slow paceful film, with no flights into fancy nor stylish

editing choices. If an era is being called back to it is an earlier

era of films, of nitrate-silver and rough-looking films like The Man

Who Shot Liberty Vallance, High Noon, or Red River (a film explicitly

acknowledged and shown in the town's cinema, the last Show of the

title).

The Westerns that are an undercurrent

to The Last Picture Show are a part of how the film draws on American

pop culture to show the decline setting into the lives of the

characters and the town.

(Arguably although cowboys are pre-pop

culture as it is normally understood, the explosion of youth-related

consumption just after the Second World War, the mythology of the

West was founded on an impressive distribution of products: news

articles about the cowboy lifestyle, theatre productions of the

exploits of the likes of George Custer, arguably one of the first

celebrities in terms understood today, recollections of battles from

those involved, books, song-sheets, and so on.)

There are several apparent call-outs to

Westerns, such as the already mentioned Red River, and scenes such as

the one in the diner where Sonny confronts Sam the Lion: pure-Liberty

Vallance. Key differences are in the ambiguities the film takes with

this heritage. A film like George Lucas's American Graffiti (1973)

deals in similar territory in use of film motifs and soundtrack, but

is much more straightforward, shifting into referencing and

sentimentalism. For all that they were part of the same wave of New

Hollywood film-makers Lucas's characters not much more developed that

those of the era being referenced, whereas Bogdanovich's in their

uncertainty and indecision transcend the pulp stock characters of

most Westerns. The decision to set American Graffiti over the course

of one night also distinguishes its fantastical elements, the fetish

for resolving all problems in a neatly packaged slot of time (the

Ferris Bueller/24 plot-line); The Last Picture Show spreads out over

an uncertain number of months mostly in daylight, so that unlike the

deeply-shadowed and neon-drenched roads of Lucas's California,

Bogdanovich's Texas is never allowed to appear as anything but a

clear, stark, moonscape where everything is as it appears.

Further comparisons between the best

critically received films of either director are apparent in the

choices made over the uses of music. Lucas constructed a soundscape

of rock n roll hits that obliterated a large chunk the film's budget:

the sales of the soundtrack proved very lucrative, also likely being

one of first big compilations of that era of music to provided a

model for others to follow. The soundtrack of Bogdanovich's film is

made up chiefly of country and western songs of the period 1951-52.

It feels accurately true to life to how the changes and survival of

certain chart songs mark the different periods of the year. Heavily

featured is the music of Hank Williams, who would die from an excess

of drugs and alcohol just after the banded time period when Last

Picture Show was set. A remarkable voice, with a Dennis Potter 'cheap

disposable pop can summon up powerfully resonant meaning, his

revolution was in the deeply emphatic tone of voice and musical

accompaniment, a divergence from the bluff and mediocre country songs

drifting into pop once the dirt had been scrubbed off (Frankie Laine,

Johnnie Ray, also present on the soundtrack). Williams also wrote an

impressive library of mournful songs: even the cheery-sounding

'Jambalaya' has its pitying line “Are you cooking something up for

me?” Williams' music meshes well with Bogdanovich's film: it

suggests the melancholy of the declining west without indulging in

cliches of riding them doggies round slow and such-like. The music is

also all used diagetically, that is it is an actual presence in the

real world of the film, pouring out of jukeboxes or car radios. The

music also suggests one of the only links between the Old West and

the New. The New West is a world where losing a football match is

enough to earn the enmity of a whole town, there is no such thing as

job security as characters drift from place to place, and the

outdoors lifestyle has become compartmentalized into the non-places

of the oilfields (despite many of the characters working there the

fields themselves never feature, only as a place someone has come

from or is going to). Though the characters dress like cowboys and

listen to cowboy music, they are many decades distant from the

lifestyle; Sam the Lion laments the loss of the empty open spaces of

his youth when he came to the country: “I used to own this land”

he declares to Sonny.

There is much that can be said about

the characters in this film, but chiefly the theme of willingness to

perform is emphasised, as a member of society and principally

sexually, as unthinkably for films a few years later this is a film

about impotence. Duane is unable the first-time around to have sex

with Jacy; Jacy's mother Lois and Mrs Popper haunt their family

homes, husbands absent; Mrs Popper's husband the Coach is implied to

be impotent, or infertile; the preacher's son is unable to do

anything more than ask the young girl he has kidnapped to remove her

underwear. The stress and boredom of life in a country without a

purpose drives people to empty frustrating acts. Forcing young people

into prescribed sexual roles leads to destruction. The monogamous

relationships embarked on by Duane and Sonny with Jacy don't work

out, confounded by the pressure on Duane to perform sexually as an

American cowboy (virility, freedom, forceful, phallic in many ways,

such as hat or gun) and Lois's gender and class pressures to

negotiate herself into a secure but maddeningly-dull housewife

existence. Sonny is a different aspect of the cowboy image, a

wanderer on the plains who is forced to turn back home by the police

when he tries to start a new life with Jacy away from Texas in

Oklahoma. Duane and Sonny do make a Western-style trek, but it is a

highly commodified and controlled one, focused on getting tanked up

in Mexico, now standard spring break fare. Duane joins the army and

leaves for the war in Korea. Sonny tries to wander but decides that

the past can't be put back together again, his friend Sam dead, the

pool hall and cinema closed, the disabled Billy thoughtlessly killed

on the road through town by a cattle truck. This realisation comes

with the cowboy-attired townsfolk gathered around Billy's body

discussing his death as if he were a dog. A cattle-truck full of

braying cows summons up images of Red River (also done via a tune at

the Christmas dance) and the callous killing of the mutineering

cattle-herders by John Wayne's Donson. Also a film about

disillusionment, Dunson is twisted to cruelty by the unrequited death

of his beloved in the indifferent cosmic West: Sonny realises this is

what has killed Billy and will kill him to. Seeing that the best he

can do is live a good and meaningful life in the present and not

become trapped in the past, he goes to Mrs Popper's house to make up

for his earlier abandonment of her for Jacy.

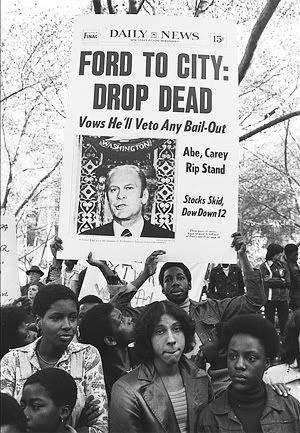

By 1971 the Western would be in

terminal decline, to revive at various points, but never again be a

meaningful force in cinema in its own right, closing with 1976's

finality-overtoned The Shootist and continuing in a slightly

zombified manner through the films of Clint Eastwood into the 1980s

and beyond. Uses of the West and the Western would be in evidence in

a few places: outlaw country harking back to the chaotic outlaw

demise of the likes of Hank Williams; country rock becoming the basis for easy listening mid 70s fare like the Eagles; the brutalist western-themed

stories of Cormac McCarthy; several waves of alternative rock drawing

on country stylings; and the somewhat moribund Americana of the 1990s

and 2000s which is unable to escape a certain feeling of stilted

properness. Country and Western the music genre, in the splitting off

of “hillbilly” music in the early 20th century by the recording

industry, has always been deeply commercialized and inorganic: modern

country is now mostly gestures (hats, beards, denims), cliches, and a

formalist approach to pop indifferent to greater meaning.

Not a coming of age story, much less a

film where people “grow up” like American Graffiti, The Last

Picture Show is a film where, in a word, Shit Happens. This feels

much more natural and true to life and is a worthy monument to the

(largely flam) revitalized New Hollywood. The film offers a route

out of he traps of declining America and small-town life, in

refocusing from rebuilding the failed cultural myths, and failed

personal relationships, of the past, to reaching acceptance not with

the present with its stultifying gender and class roles, like

American Graffiti, but finding acceptance and solidarity with each

other.